Certainly, wine is neither an ordinary beverage nor a common foodstuff. We state this—and this holds especially true for readers hailing from the “Old World”—because, in all probability, if we find ourselves here together, it is because our personal lives, or those of our family members, distant ancestors, or dear friends, are linked in some way to the management of vineyards, the production of fine bottles, or the presentation to the world of work done with love and mastery.

We know this because, when thinking of the land that raised us, we almost instinctively associate it with its most representative grape varieties, or with the landscape punctuated by the unmistakable profile of the vine rows. And we are certain of it because the most joyful or meaningful moments of our existence have been sealed by a celebratory toast, a shared tasting, or a slow sip fertile with thoughts and emotions.

From the sweetness laden with expectations that opens the tasting with the warm tones of a late spring day, we moved to the more vivid and stark vibrations of salt and mineral notes, only to arrive at the bracing and “fluorescent” freshness of acidic components, which call everything back into question.

And when the sip slides over the tongue until it reaches the basal portion, there the wine meets the characteristic inverted “V” of the taste buds dedicated to the reception of bitterness: the most reflective, “twilight,” and “autumnal” of the five fundamental elements of gustatory perception.

It is precisely there that bitterness manifests itself at the close of the experience, determining its duration and intensity, sealing its memory.

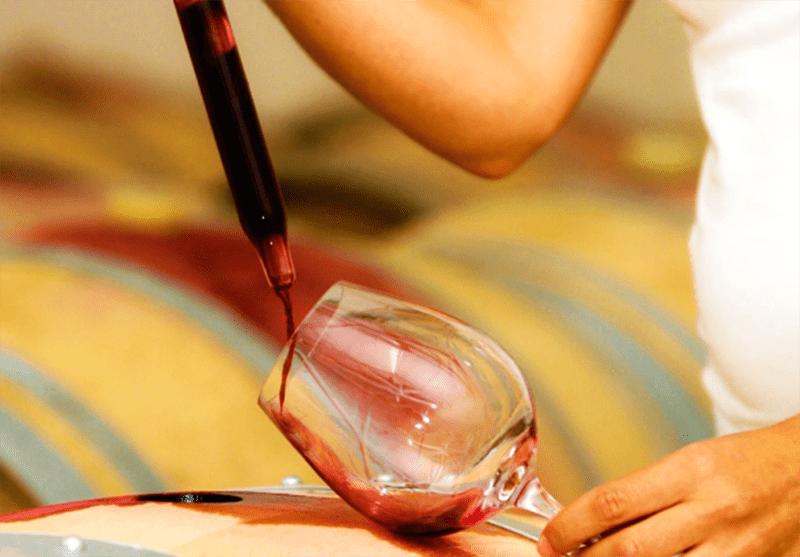

To what, then, are the bitter perceptions that wine can express linked? To the coexistence of multiple factors, but primarily to the presence, within the berry, of chemical compounds belonging to the group of polyphenols, particularly tannins. These are found in the skins, in the seeds, and also in the wooden walls of the vessels used during aging.

The intensity of bitterness will thus depend on the duration of contact between the must and the pomace, the ripeness of the grapes, the length of the refinement period, the type and size of the wood, and therefore the surface area of contact between the wine and the barrel. The age of the wine also plays a fundamental role: polyphenols modify their expression over time through phenomena of polymerization and condensation that transform the initial sensory perception.

Furthermore, factors such as the ripeness of the grapes at the time of harvest and the alcohol content of the wine contribute to this. In such an articulated dynamic, it is evident that a wine's ability to express bitterness—and the manner in which it does so—becomes a distinctive trait of identity and personality.

The bitter note recalls other sensory experiences: nuances of tobacco, veins of dark chocolate, the severe echoes of coffee. The mind associates and travels: to the elegant scent of sandalwood, to the bite of radicchio under the snow, to the cinchona bark of an ancient vermouth, to the wild resin of a gin, right down to the ferrous inflections of a raw artichoke heart.

It is all the art that seeks man through nostalgia or the naked truth of reality. It is the tango that rises with passion and pain, it is the jazz double bass grumbling in the shadows, it is the blues of Robert Johnson, the dark lyricism of Nick Cave, the elegant restlessness of Leonard Cohen. Bitter is what becomes great by starting from the small, from the true: the portraits of Caravaggio, the still lifes full of ripe fruit, the pitiless faces of Goya. Bitter, poignant, and vital are the stories of the marginalized: the poor Irish of Angela’s Ashes, the broken and tender family of La Storia, Verga’s defeated characters, the torments of Dostoevsky's protagonists, the nostalgia of Montale, the disenchantment of Céline.

And then Proust, with his “intermittencies of the heart,” and that sudden shiver that a current sensation can recall from the past. Bitterness is a mirror of man's incompleteness, but also a promise of depth: because it contains the idea that beyond the present, there exists a trace of our being, a beauty born precisely from lack.

And it is thanks to the bitter notes that reflection can complete the design, illuminating the meaning of things with oblique light.

Thus, even the tasting of the wine we love most, in its bitter aftertaste, resists and persists beyond the moment, carrying with it sweetness and salt, freshness and warmth. And it leaves us, in the end, with the indelible memory of a special label, of a season of life we will not forget, of our wisest and most fertile glass.

Roberto Cipresso

Wine Consultant and Author. Expert in terroir viticulture